The Mahogany That Built Britain And Bankrupted the Caribbean

By Nyan Reynolds

News Americas, NEW YORK, NY, Fri. Jan. 22, 2026: Walk into any Britain manor house built in the eighteenth century, and your eyes will almost inevitably find it. Along the doors, curling up the stair rails, lining the walls, and framing mirrors, a deep reddish-brown glow catches the light. Mahogany!

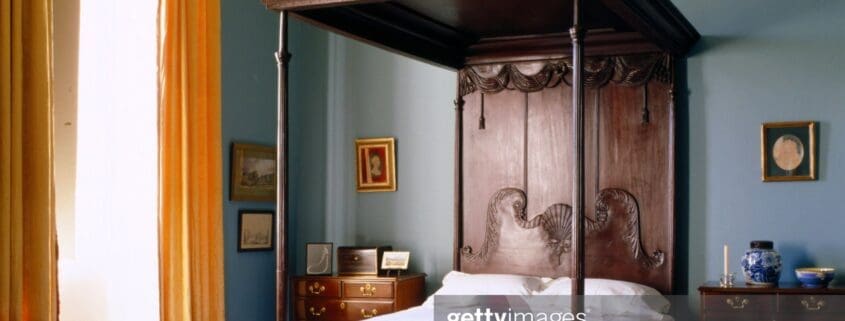

The Countess’ Bedroom at Florence Court. The view shows the mid eighteenth century Irish four poster mahogany bed with the Queen Anne chest at the end & a chest of drawers by the side.

For Britain’s elite, it was never just wood. It was a symbol of wealth, power, and permanence. Yet the story behind that polished glow is far more complicated, and far more devastating, than the walls of any country house can reveal.

Mahogany did not simply arrive in Britain. It was cut from forests in Jamaica and Haiti, from landscapes where people would never see the true value of what was taken from beneath their feet. These places are now regularly described as developing nations. Yet for generations they supplied some of the finest hardwood in the world, only to watch that resource leave their shores and enrich distant markets.

This is a chapter of Caribbean history that rarely appears in schoolbooks. It should.

The Wood that changed British Rooms

Before Caribbean mahogany entered British workshops in any serious quantity, furniture makers relied on oak, walnut, and pine.

Oak had dominated for centuries. It was strong, familiar, and durable, but it carried a heavy and somewhat muted appearance. Walnut rose in fashion toward the end of the seventeenth century. It offered a more attractive grain, but it could split and was vulnerable to insects. Pine was plentiful and cheap. It was often used for hidden structures or for less expensive furniture, but it lacked the prestige needed for elite interiors.

Mahogany transformed that craft world. The West Indian species described by botanists at the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew combined strength with beauty. It resisted rot, worked smoothly under tools, and could be polished to a deep glow that looked almost like still water. It was tough enough for shipbuilding and yet refined enough for the finest drawing rooms.

The turning point came in the early seventeen hundreds, when captured Spanish ships brought mahogany planks into British hands. Shipbuilders noticed how well the timber withstood saltwater. Cabinetmakers noticed how stunning it looked indoors. Within a few decades mahogany was no longer a novelty material. It had become the preferred wood of the British upper class and an essential part of Georgian taste.

Britain’s Hunger for Timber and the Turn to the Caribbean

Mahogany’s rise cannot be separated from a wider imperial strategy.

By the early eighteenth century, Britain’s forests were under intense pressure from shipbuilding, construction, and iron production. The island simply could not provide all the timber a growing empire demanded. Parliament answered that problem by looking outward.

In seventeen twenty-one the Naval Stores Act removed import duties on timber and other materials coming from the colonies. That incentive encouraged merchants and shipbuilders to look west rather than toward European forests. Colonial hardwoods became strategic resources, and mahogany quickly moved to the center of this new supply system.

A few decades later, the Free Ports Act of seventeen sixty-six opened select Jamaican harbors to foreign ships, including French traders from Saint Domingue, present day Haiti. This legal change allowed timber from non-British colonies to pass through Jamaican ports and then on to Britain. On paper this looked like commercial flexibility. In practice it deepened Jamaica’s role as a processing and redistribution hub for West Indian hardwoods rather than a place where that wealth stayed and multiplied.

Jamaica and Haiti at the Center of the Trade

By the middle of the eighteenth-century Jamaica had become the most important supplier of mahogany to Britain.

Customs data examined by furniture historian Adam Bowett show that between seventeen sixty-four and seventeen seventy-four Jamaica provided more than ninety percent of Britain’s recorded West Indian mahogany imports. In some years the share was even higher.

Behind those figures was relentless and dangerous labor. Logging crews made up largely of enslaved Africans cut enormous mahogany trees that had taken centuries to grow. They dragged logs that could stretch twenty feet and weigh several tons through dense forest, often with the help of oxen. In interior regions they were forced to build rough roads simply to move the timber to rivers or coastal inlets. From there the logs were floated or hauled to ports such as Kingston and Montego Bay, where they were loaded onto ships bound for the Atlantic crossing.

Haiti, then the French colony of Saint Domingue, entered the British mahogany system in a more indirect way. The Free Ports Act permitted mahogany from Hispaniola to be shipped into Jamaica and then re-exported. As historian Neville Hall has noted, by the seventeen eighties a significant share of the timber listed in British records as Jamaican actually originated elsewhere in the Caribbean and simply passed through these free ports.

The ledgers suggest a single source. The reality was a wider Caribbean of extraction.

The Numbers that Reveal the Scale

The trade in mahogany was not a minor sideline. It was huge.

British customs records and Bowett’s research reveal a dramatic rise in imports.

In seventeen twenty-four Britain brought in a little over one hundred and fifty tons of mahogany. In seventeen twenty-five that figure had nearly tripled to more than four hundred tons. By the late seventeen eighties annual imports were measured in many tens of thousands of tons. Between seventeen eighty-four and seventeen ninety Britain imported more than one hundred twenty-four thousand tons of mahogany. In seventeen eighty-five alone more than ten thousand tons came from Jamaica.

Prices rose along with demand. In the seventeen thirties London prices averaged only a few pence per foot. By the middle of the century, they had roughly doubled. Around eighteen hundred the finest logs could command about two shillings per foot, an increase of several times the original price in less than a human lifetime.

Even after paying for freight and insurance, merchants made handsome profits. Freight typically added a small amount per foot, and marine insurance in peacetime ran only a few percent of the cargo’s value, although it spiked during war. Once those costs were covered, the profit margin on prized hardwood remained high.

Translated into present terms, Britain was importing timber worth the equivalent of millions of pounds each year. Much of it came from Jamaica and through Jamaica from Haiti and other islands.

Chart 1 – British Mahogany Imports: Jamaica vs Total (1724–1790)

Resource stripping and ecological loss

The ecological cost became visible even to observers within the colonial system.

By the seventeen sixties, planter and historian Edward Long was already warning that easily accessible coastal mahogany in Jamaica had been exhausted. Loggers had to push further and further inland. That meant greater labor costs, more roads cut through forest interiors, and more disruption of soils and watersheds. What had once been large continuous forest became scattered stands separated by clearings, paths, and erosion.

In Haiti the story continued into the nineteenth century under a new and cruel pressure. After the Haitian Revolution and independence in eighteen hundred and four, France forced the new Black republic to accept an independence debt in eighteen twenty-five under threat of renewed war. To service this obligation Haiti expanded exports of timber and other cash commodities, including precious woods such as mahogany. Environmental historian Richard Grove and others have shown how this debt driven extraction accelerated deforestation and entrenched economic dependency.

In both islands, forests that might have supported long term local industries and ecological resilience were sacrificed to meet the demands of foreign creditors and distant markets.

Who Gained and Who Lost

Chart 2 – Jamaica’s Share of British Mahogany Imports (%) (1724–1790)

If you stood in a London showroom in the late eighteenth century, the benefits of this trade would have seemed obvious.

Mahogany underpinned a thriving furniture industry, furnished the homes of the wealthy, and helped shape an image of British taste and refinement. Shipbuilders valued its durability for naval and merchant vessels. Merchants, shipowners, and investors profited at every stage of the process.

On the Caribbean side of the equation the picture looked very different.

The value of the timber flowed outward. Local economies saw little structural development from this steady extraction. Enslaved laborers endured the backbreaking work of felling, hauling, and loading vast logs without any share in the profits. Even free people of color who participated in parts of the trade operated inside a system that channeled the greatest returns to Britain and other European centers.

Postcolonial economist Walter Rodney described this pattern as a central mechanism of underdevelopment. Resources are taken from a region without equivalent reinvestment, leaving behind economies that are structurally weak, dependent, and vulnerable. The story of mahogany in Jamaica and Haiti follows this pattern with painful clarity.

Why we Rarely Hear This Story

Sugar, coffee, and bananas dominate the usual narrative of Caribbean economic history. Timber, and mahogany in particular, often appears only in passing or not at all.

This absence matters. It narrows how Caribbean history is understood. When resource extraction is presented mainly through plantation agriculture, we miss how deeply colonial economies reached into forests, mountains, and coastal ecosystems.

Historian Verene Shepherd and others have argued that colonial narratives often highlighted commodities that supported a certain image of the plantation system while minimizing industries that revealed a broader and more flexible web of exploitation. Timber was essential for ships, buildings, and luxury goods, yet its role in the exploitation of Caribbean environments and people has remained relatively obscure in public memory and in many school curricula.

That silence is itself part of the legacy of empire.

A Jamaican Childhood in the Long Shadow of Mahogany

For me this history is not just an intellectual interest. It connects directly to my own life.

My Jamaican family was poor. Not simply living on a tight budget but living with real and constant deprivation. We counted every dollar. We stretched every meal. We watched possibilities slip away because the entry costs were always out of reach.

Many of my friends lived the same way. My grandparents had lived that way for most of their lives. At the time it felt like an unfortunate normal, something we simply had to endure.

Only later, as I began to study the economic history of Jamaica and Haiti, did I start to see those personal experiences as links in a much longer chain. When mahogany and other resources were stripped from our landscapes and shipped abroad, the profits were not used to build broad based prosperity at home. They built estates, institutions, and industries elsewhere.

So, when I ask what my ancestors might have built if the wealth of their forests had been harnessed for their benefit, I am not indulging in fantasy. I am asking a question that belongs at the center of any honest conversation about global inequality.

Too often the modern poverty of countries like Jamaica and Haiti is treated as though it sprang from nowhere or from purely internal failures. In truth it is deeply connected to histories of extraction in which mahogany played a significant role.

The Past is Not Finished Business

People sometimes talk about the past as if it lived only in museums or in carefully bound history texts. Yet history is also present in very concrete ways.

It appears in under-resourced schools and hospitals. It appears in eroded hillsides where forests once stabilized soil and climate. It appears in national budgets shaped by old debts and unequal trading relationships.

The underdevelopment that I saw growing up was not a random misfortune. It was part of a pattern that stretches back to the colonial period, when land and labor were organized around the enrichment of distant powers. Mahogany is one thread in that pattern and following that thread helps us see how the past has been carried into the present.

Why this story still matters

The journey of mahogany from Caribbean forests to British drawing rooms is about far more than beautiful furniture.

It is about power, about who gets to decide how land and labor are used. It is about wealth, about where profits accumulate and where they do not. It is about memory, about whose experiences are recorded and whose are omitted.

Today Jamaica and Haiti are still labeled developing nations. Policy makers and commentators discuss their challenges in terms of governance, crime, education, and external shocks. All of those factors matter. But any analysis that ignores centuries of structured resource extraction is incomplete.

To tell the story of mahogany honestly is to restore part of what has been missing from that wider conversation. It helps explain how magnificent paneling in English houses is connected to exhausted forests and intergenerational poverty in the Caribbean.

Reclaiming the narrative

Mahogany’s legacy in Britain is easy to see. It sits in antiques showrooms and museum galleries, in paneled libraries and sweeping staircases, polished and preserved as part of the nation’s cultural inheritance. The wood is admired for its craftsmanship and beauty, rarely for the conditions under which it was obtained or the worlds it passed through before reaching those rooms.

Its legacy in Jamaica and Haiti is far harder to recognize, precisely because it is not displayed. It survives in altered landscapes, in hillsides where forests once stood thick and continuous, in river systems reshaped by erosion, and in rural interiors stripped of resources that might have supported lasting local industries. It also lives in economies that exported immense value yet retained little of it, leaving behind patterns of poverty and dependency that have proven remarkably durable.

Restoring this history is not simply an academic exercise or a matter of adding footnotes to the past. It is a step toward historical justice. By naming the exploitation, tracing the movement of wealth from Caribbean forests to British drawing rooms, and linking those processes to present economic realities, we begin to confront what was taken and how its absence continues to be felt.

For me, reflecting on mahogany’s story is inseparable from reflecting on my own life and on the lives of those who came before me. It is an act of remembrance and of responsibility. We cannot regrow every tree that was felled, nor can we rewrite the ledgers that recorded extraction while erasing human cost. But we can refuse the silence that has long surrounded this trade. We can insist that these histories be told clearly, honestly, and widely.

Only then can new chapters be written on a foundation of recognition rather than erasure. Only then can the forests and communities that remain be valued not merely as reservoirs of exportable resources, but as places with their own histories, their own dignity, and their own right to thrive.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!